For current food writing, please check out and subscribe to my Substack website, https://sarahduignan.substack.com/

Here you will find biweekly essays on food, health and wellness culture, climate change, and anthropology.

For weekly essays on food, health, and environment, check out host Sarah Duignan’s new Substack Newsletter - AnthroDish Essays at sarahduignan.substack.com

For current food writing, please check out and subscribe to my Substack website, https://sarahduignan.substack.com/

Here you will find biweekly essays on food, health and wellness culture, climate change, and anthropology.

As a food podcaster, you’d think that I would run out of steam listening to more shows about food, but sometimes it’s quite the opposite. I’ve found some shows that constantly push my own thinking in new directions, and inspire me to expand the conversations I have on the show and with my friends, family, and students, too! I’ve compiled a list of my current go-to food podcasts below, though it is by no means comprehensive. There are some incredible food podcasts out there, and I’m also a big fan of podcast that fall outside the range of food too (shocker! haha) - so perhaps I will come up with a more general round up of my favourite podcasts down the way.

I will say that I avoided listing podcasts that are traditionally produced through more widely known networks, or the stalwart food podcasts that are often featured on top lists… there’s just something about a small independent group of folks (or an individual working away at this by themselves) that makes me much more excited to listen. Plus, it gets boring seeing the same 10 food podcasts on every list. And I know just how much time and energy the folks on this list below are putting in for the sake of creating some audio magic and sharing food knowledge and stories!

The moment I heard the trailer for this podcast in May, I was already eager for more and sharing it with as many friends as I could. Hosted by Nico Wisler, this podcast explores the idea of “queer food” in all of its limitless forms. They talk with farmers, chefs, activists, historians, seed savers, and business babes to explore the joyful, messy, radical magic that happens in spaces where queerness and food intersect. Nico also has a love for extra garlic that speaks to my soul!

Episode to Start: Episode 7, The Corners of Their Mouth

Nico chats with Robin Elan and LM Zoller (authors of The Corners of Their Mouth) to explore what queer food is and what it can be, what LGBTQ+ bloggers bring to writing, and those ridiculous and harmful gender reveal cakes.

Toasted Sister is a show I’m always excited to listen and learn from. After colonial contact, Indigenous foodways and knowledge were devastated and replaced with foods that were far removed from Indigenous Peoples. Host Andi Murphy talks with Native chefs and foodies about what Indigenous cuisine is, where it comes from, and where it’s headed. In individual interviews, the show explores how Indigenous cuisines are used to connect their people to their origins and traditions. Murphy is Navajo, based out of Albuquerque, and freelance multimedia journalist and a full-time producer for Native America Calling, which is a national call-in show about Native issues and topics. The Toasted Sister website also has some incredible videos and recipes of Indigenous cuisines, and easily the best podcast art I’ve ever come across.

Episode to Start: Episode 6, Dr. Elizabeth Hoover — Food Sovereignty.

Andi interviews Dr. Elizabeth Hoover (Mohawk and Mi’kmaq), who travels around asking Indigenous people what their definition of food sovereignty is. This is a great episode if you’re new to learning about Indigenous food sovereignty, as they explore just how vastly different it can be for different Indigenous Peoples, and the varied ways that communities are starting to revitalize their own food sovereignty.

You might already be familiar with Katie Quinn’s Keep it Quirky podcast if you’ve been listening to AnthroDish for a while — she was a guest back in January! Katie is one of the coolest and most fun people to interview, but is also an incredibly gifted host and digital media expert.Katie is the creator of food and travel videos on her awesome YouTube channel, QKatie, as well as a trained chef with. Her motto throughout all her work is, you guessed it, to keep things quirky! On her podcast, she looks at the Venn diagram of food, entrepreneurship, and inspiration with creatives and entrepreneurship. There isn’t a singe episode that has left me without a new idea for a project or a way to build and grow as a creative. She finds these wildly fascinating guests whose passion for their work just shines through the interview each time - and I think Katie’s natural joy and curiosity are a testament to how consistently fun and powerful these conversations are!

Episode to Start: The episode I’d recommend checking out to jump into this show is “The Women We Learn From, with Anastasia Miari of Grand Dishes” Anastasia explores the inspiration behind starting the GrandDishes cookbook project, which features stories of and recipes from grandmothers all around the world… cool, right?! Be prepared for your mind to be flooded with inspiration!

This podcast is a more recent find for me, and quickly becoming one of my all-time favourite shows. The FFP podcast series documents the rise of women in agriculture. It aims to serve as a platform for women to discuss agricultural issues, and give power to the traditional, cultural, and experience-driven knowledge. Hearing directly from female-identifying farmers makes you feel much more connected to food production, and helps you interweave culture, history, tradition, and change within agriculture and food.

Episode to Start: Afro-American Storytelling with Queen Sugar author Natalie Baszile

Natalie Baszile, author of Queen Sugar, discusses writing stories of African American experience with land ownership, intergenerational wealth and inheritance, land loss, mass incarceration, police brutality, and other systems of oppression. It’s an eye-opening discussion that I can’t stop thinking about.

Here’s another former AnthroDish guest… perhaps I’m a bit biased in terms of the shows I love, but for good reason! Copper & Heat is a James Beard-winning podcast produced by Katy and Ricardo Osuna, and based in San Francisco. The first season, Being a Girl, is a sound-rich narrative documentary that focuses on why women only represent 19% of chefs, and only 7% of head chefs across the culinary world. They use Katy’s experience working in the Bay Area’s Michelin-starred kitchens, as well as stories of other kitchen employees to uncover the ways that traditional masculinity has impacted kitchen culture. Plus, she uses her anthropology background to question what is understood as “normal” practice and why.

Episode to start: As this is a serial narrative-style podcast, I’d recommend starting this podcast right from the start (season 1 has 8 episodes, and season 2 is coming soon!).

Food Focus is hosted by Michael von Massow, a professor at the University of Guelph. It’s a show that intends to discuss, challenge, and learn about topic issues around the food system. Mike’s own work looks at consumer choices and trends in food systems, which is something I find endlessly fascinating. I really appreciate his broad and complicated views of food, and the choices and behaviours we make around them. It lends to really interesting and thought-provoking discussions that leave you (or me!) excited to think about new ideas and approaches to food issues in Canada.

Episode to Start: Extraterrestrial Eats — Growing Food in Space

I mean… the title alone should explain what makes this such a cool episode! Host Mike interviews guest Mike Dixon, a professor in the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Guelph to discuss the technical challenges that come with growing food in space, and how these ideas can extend to food insecurity solutions back here on earth.

Okay, okay, I promise this is the last former AnthroDish guest I feature on here… or is it? Heheh. Food Heroes Podcast is a total staple for me. Host K80 Jones takes a sustainability lens to key food issues, using one-on-one interviews with food experts to explore their work and what make them a food hero. She has a background in food research and development, but I find she always uses multiple lens to explore her guest’s experiences. Plus, she’s super real, and super funny. She calls it like it is, and isn’t afraid to ask questions when she’s learning something new. I think that’s really important trait for a podcast host, given that we’re acting as the middle-person between audience and expert. It’s important to remember the audience’s level of knowledge and when to ask the questions that are probably popping up in their minds as they listen.

Episode to Start: Episode 26 - Sean Lenihan of the Honest Bison: Honesty and transparency in the meat industry.

One of my recent favourites was this episode on increasing transparency in the meat industry. I’ve been a vegetarian for over a decade now (most of my adult life!), so my meat knowledge is LIMITED (I recently had to ask a friend to teach me how to cook bacon for my daughter…). This episode opened up my mind to some of the key challenges that the meat industry is facing going into the 2020s, and what Sean thinks is integral to a successful and sustainable meat industry.

Am I allowed to choose favourites? Yes? Okay great. Without a doubt, this podcast by Kaila Tova is my absolute favourite podcast to come out of 2019. Your Body, Your Brand is a serial documentary podcast that asks really tough and important questions of the fitness and wellness movements: why are people (and particularly women) dropping out of the workforce to become health coaches? Why are we so bought into the idea that our bodies are more lucrative than our minds, and why do people keep reinforcing this with their social and financial capital? Each episode digs deeper into the complicated world of healthy eating, bodies as brands, eating disorders, social and economic capital, and more. And the conceptual photos for each episode are so thoughtful and tongue-in-cheek.

Episode to State: Start with episode 1, as this is a documentary-style podcast that builds on key ideas from one episode to the next. It’s SO good, I’m excited for you to listen to it.

“Foodie,” a term once relegated to food writers and gourmet appreciators, now encompasses a broader group. Many of these new foodies like to keep an online record of their eating habits: posting photos on Instagram or reviews on Yelp.

What many consider to be a hobby, however, can also be an indictment of lurking Western values around health and culture that appropriate, marginalize and exclude crucial voices.

The rising cultural appreciation of what we eat in North America comes with increasing connections between how our food choices mark our identity. Are we sustainable consumers, eating organic and non-GMO foods that are healthy for us and our environment? Or are we social media users concerned with trendy foods, ingredients and cuisines?

More importantly, how does the new foodie culture complicate racial and socioeconomic issues?

In the last decade, mass foodie-ism has grown into a social awareness of food systems and a heightened appreciation of taste. Early in the 2000s, food writers like Michael Pollan and Marion Nestle highlighted North America’s unsustainable food systems and challenged the public to be engaged with what and how they ate.

This conscious awakening grew even more through documentaries like Food, Inc., and food television like Chef’s Table. With that, food morality and food politics really blossomed.

The late Anthony Bourdain said the North American food fascination is connected to its relative cultural youthfulness: less than 300 years old. Bourdain argues that we’re in the process of growing up and learning what older cultures have known for a long time: food is more than just food. It’s conversation, politics and social status.

Foodie movements, like Slow Food, are often rooted in undertones of morality. For example, common words used to describe food on vegan or health blogs are: natural, organic, pure, unprocessed. The implication is the opposite: that foods that don’t fit into this category are bad.

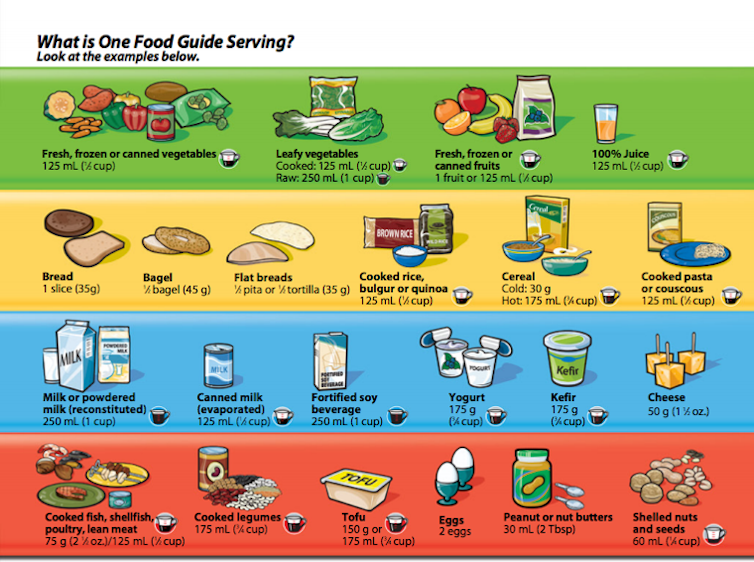

Canadian attitudes towards some traditionally basic ingredients has shifted. For example, milk is no longer a main recommendation on Canada’s updated Food Guide. Lean fats are encouraged and less salty or sugary foods are recommended to maintain a healthy diet. Individuals who can’t live up to these new expectations are blamed for their own failure to adapt.

The moral superiority expressed with these diets can act as harmful barriers to some, socioeconomically. Also, the appropriation of global cuisines that come with foodie culture can work to maintain structural racism.

The “Five White Gifts:” flour, sugar, salt, milk and lard. are ingredients that are full of historic injustices and ongoing colonial legacies. These five foods were given out in ration boxes by the government of Canada during the 1940s to Indigenous families living on reserves.

The Canadian government believed these “gifts” would make up for the lack of access to traditional hunting and fishing spaces. These ingredients became staple foods for many Indigenous families and contributed to forcing a disconnect for communities from their traditional food sources. This caused ongoing health concerns, most notably higher rates of type 2 diabetes.

Food morality can reinforce racially-charged power structures and food gentrification means that some communities can no longer afford their own foods.

Chef Andrew Zimmern positioned himself as a cultural navigator of Chinese cuisine. Last fall, his launch of Lucky Cricket restaurant in a Minneapolis suburb has been raised as an example of food appropriation. The restaurant serves Chinese foods to a mostly white community, focusing on small plates, “adventurous eating” and organic, local ingredients. Zimmern, concerned that the neighbourhood he served wouldn’t understand his food, aimed to “introduce them to a real duck roast.”

After public outrage of his cultural appropriation ensued, Zimmern responded in a Facebook post saying he believes his role is “making invisible communities, cultures, tribes and businesses visible.”

This Westerner-as-cultural-expert mentality maintains imperialist notions, similar to the idea of early Western explorers “discovering” the New World. It’s a one-way exchange where “the Westerner” gains “insider” knowledge and has the power to re-purpose and profit from these foods.

Toronto-based writer Lorraine Chuen explored these intersections of food, race and power by researching who is considered to be an authority on “ethnic recipes.” Chuen sampled recipes from the New York Times recipe section and found those writing about cuisines from different cultures were white writers. Therefore, in the example of the publication and circulation of the New York Times recipes, it is often white foodies who control how dishes are cooked at home and interpreted, thereby erasing people of colour from their cultural heritages.

It may be easy to critique food personalities perpetuating existing power dynamics by being “benevolent” authorities and translators of global foods. A more difficult task is to critically self-reflect. How might we as Instagram-users perpetuate harmful attitudes and practices?

Social media is a useful everyday tool for foodies to solidify their social power. Foodies impart knowledge through visuals and reviews that fuel certain spaces as the more authentic dining experiences. Mass-foodies are then crowned as the primary sources for other people’s indirect knowledge of “good” food.

What’s a food-loving person to do?

We can think more consciously about how we use food as a symbol for our own self-expression. We can examine how we morally position ourselves and our food choices. We could skip the foodie influencers who feel the need to translate cuisines of different cultures. We could support an authentic food industry.

Shows like David Chang’s Ugly Delicious are tackling harmful food stereotypes. Indigenous chefs like Rich Francis of Seventh Fire Catering are fostering cultural healing and reconciliation through food.

If we want to truly make food and life more sustainable, we should think about the power dynamics of our food. If we respect the humanity of the communities we interact with, our food experiences and global curiosities are enriched by all cultures on their own terms and power.![]()

Sarah Duignan, PhD Candidate, Host of AnthroDish Podcast, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This piece originally appeared in The Conversation Canada.

Canada’s Food Guide is being revised. After a three-year consultation process, the guide will be published within weeks. Sadly, economic and political agendas will likely continue to make its dietary recommendations unachievable for many Canadians.

As a biocultural anthropologist, I explore how nutritional health goes beyond physical health. Social factors like income and proximity to grocery stores have an impact, as do cultural values and knowledge.

Why then, in a country as culturally diverse as Canada, is there such a surprising lack of culinary representation in our food guide?

The food guide has long been rooted in economic agendas. The 1942 Official Food Rules for Canada were developed to encourage Canadians to eat more, despite food rationing during the Second World War. This was to combat malnutrition and to strengthen soldiers and industry workers. Despite seven changes to the guide between now and then, there have been no suggestions to eat less.

Early drafts of the new guide indicate that the conventional four food groups will be reduced to three — wholegrain foods, fruit and vegetables and protein foods (incorporating the traditional meat, fish and dairy).

The drafts suggest the guide will remain focused, however, on the nutrients that individual bodies should consume. The food guide does not appear to tackle the important economic, social and cultural barriers many individuals and families face to accessing healthy food.

During a 2013 visit to Canada, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier de Schutter, expressed serious concerns over the severity of food insecurity and hunger across the country.

Food security is defined as the availability, accessibility, affordability and appropriateness of foods for households.

Notably, de Schutter voiced concern about the lack of social protection programs and high rates of food insecurity for low income households, Indigenous populations living off-reserve and new immigrant families.

Early prototypes of the Food Guide reveal a continued focus on fresh produce. And yet frozen produce is cheaper and still reliably nutritious. And when you’re stressed about money or live far from a Whole Foods, you’re unlikely to prioritize quality over quantity of food.

The new guide could offer more dominant visuals of affordable food alternatives — for example frozen spinach cubes beside fresh varieties — to connect to more Canadians.

The guide should also think about healthy foods that are culturally appropriate. Incorporating traditional Indigenous foods (for example game meat, corn soup or wild blueberries) or foods that would be recognizable to newcomers to Canada (such as plantains or cassava for Central American families) would help more communities recognize their own diverse histories and cultures in the Food Guide rainbow.

If we are serious about reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, then this should also be reflected in what foods we recommend as healthy. Health Canada does have an Indigenous-specific food guide, but the language and visuals suggest that this is a “complement” to the main guide. Its grain recommendations, for example, ignore the fight some Indigenous communities are having to reclaim their pre-contact cuisine.

Food sovereignty is the right to healthy, sustainable and culturally appropriate food, and for communities to define their own food systems. Incorporating traditional foods from a variety of Indigenous cultures (for example wild rice, char and fiddleheads) into the main guide would make the recommendations more reflective of the diverse values and cultures that make up our country.

More importantly, it would also help to shape realistic food recommendations for communities where certain foods are more accessible and affordable, particularly for those living off-reserve. In turn, foods that are culturally and physically nourishing may help improve chronic health conditions and promote cultural healing.

Throughout the evolution of the Canada Food Guide, agricultural industries have lobbied for certain foods to be prioritized. The 2007 version drew concerns from health experts, as it suggested a half cup of fruit juice was equal to a serving of fruit. There was also worry that the guide encourages people to eat too much meat and dairy.

The 2019 update of the Canada Food Guide makes important changes by removing fruit juice recommendations and encouraging Canadians to drink fewer sugary beverages. Yet concerns remain about the agricultural industry’s influence.

“Secret” memos from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) stated that emphasis on plant-based proteins would have “negative implications for the meat and dairy industry.” The AAFC also argued against plant-based diets being more sustainable, claiming that the beef industry was making sustainability efforts.

In 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food recommended the government work with industry to “ensure alignment and competitiveness for domestic industries.” This may suggest that sustainability is not on the government’s menu.

But this is also an era of Canadian history defined by climate change, harmful government actions against Indigenous sovereignty and food-insecure families.

And it’s not an impossible task to positively change national food recommendations. Brazil’s 2014 food guide framed diet as “more than just nutrients,” embracing food as a natural part of social life. The guide recommends reducing processed foods (like chips or soft drinks), and increasing culturally appropriate foods (like local plants) that support social and environmental sustainability.

Brazil stated that dietary recommendations need to be tuned into their times, responding to changing food supply and population health. Reacting to social, cultural and environmental changes to food systems isn’t just good for a population’s diet — it makes for more resilience during climatic change and hardship.

Perhaps it’s time for Canada to move away from individual nutrients and frame healthy diets as dependent on socially and environmentally sustainable food systems.![]()

Sarah Duignan, PhD Candidate, Host of AnthroDish Podcast, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hey everyone!

Not sure if blogs are still relevant and enjoyed in 2019 given how fast technology and media has been moving in recent years.

HOWEVER, I have felt increasingly the urge to expand AnthroDish in certain ways, and one of them is by setting some more time aside to reflect on my own ideas around food. I adore the guests that I have on, but I always try and shape conversations around their perceptions, experiences, and knowledge. And while I certainly align with many of their ideas, I’m admittedly a bit nervous to put my own thoughts out there on the line. So writing felt the most natural way for me to start this, as writing was always my first love (before anthropology, even - shocker!).

A personal goal of mine this year was to start writing more in different news outlets. I’ve started working with the amazing editors over at The Conversation Canada and aim to keep writing science communication pieces where I can! So if you have any thoughts about where I could, drop me a line and let me know.

This particular space I’ll be using to share my reflections and opinions about food, anthropology, and sometimes even motherhood! Exploring what’s making the news and digging into the anthropology of it all.

So stay tuned, I hope you enjoy what’s about to come for this space!